Tutu, the portrait of the Ife royal Princess Adetutu Ademiluyi, was found in a London flat in the home of a “perfectly ordinary” family, said Giles Peppiatt, director of modern African art at Bonhams. Until now, Nigerians and the global art world considered the works lost forever.

The masterpiece’s price was estimated at £200,000 – £300,000. The bidding took place both in London and Lagos simultaneously.

Tutu, a portrait of the Ife royal Princess Adetutu Ademiluyi painted in 1974, led Bonhams Africa Now sale in London on Wednesday 28 February at location 101 New Bond Street London at 5.00 p.m. London time, and in Lagos at Wheatbaker Hotel, Ikoyi, at 6.00 p.m. Lagos time.

The buyer of the painting, as at the time of this report, has not been disclosed.

History of TUTU

Ben Enwonwu never sold Tutu. The painting had a special meaning for him. He kept it in his possession—in his bedroom, I’m told—for 21 years until his death in 1994. It was reported that several of his patrons found it difficult to get him to show them the piece and, later, one of his collectors, Norma Jackson-Steele, said that Enwonwu had declared Tutu his masterpiece. Earlier this decade, there was an extensive unsuccessful search for the original Tutu, but it was whispered to me by a reliable source (as journalists would say) that it is still in the possession of one of Enwonwu’s children.

Adetutu Ademiluyi, the woman who sat for the portrait that is currently the bestselling print in Nigeria, was a member of the Ile-Ife royal family. The Ooni of Ife, at the time, was one of Enwonwu’s patrons. One day Enwonwu, while on a visit to the palace, saw Adetutu, one of the Ooni’s granddaughters, and the rest is history. I can’t help but wonder what Enwonwu saw on that first meeting that made him determined to paint her despite her parents’ hesitation to give their approval, and if he had any inkling of how important she would be to his legacy.

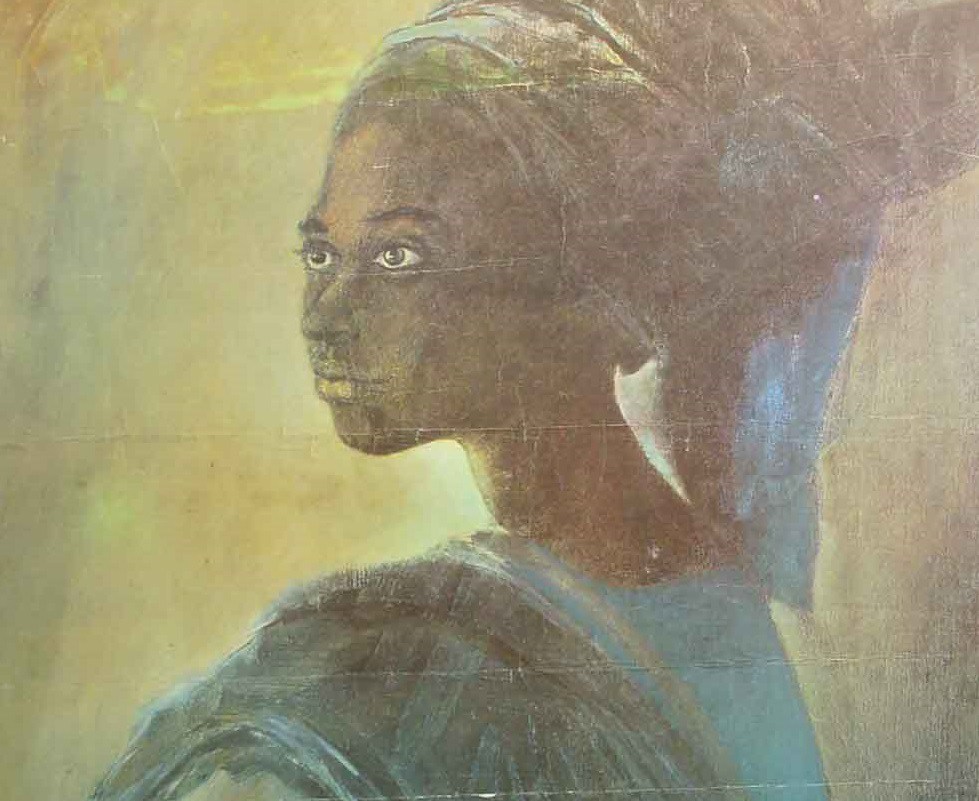

From the moment my brother-in-law showed me Tutu, I became intrigued by it—obsessed even. I read the little I could find on the piece and on Adetutu Ademiluyi. Even now, I ponder on why I find her so compelling. And what do I see in her eyes: Is that confidence? Is that defiance? Is that hope? Is there a trace of fear? Here is a portrait of a classical beauty that invites you to look beneath the surface, and gives off a sense of mystery. In all my imaginings, I not only considered what Enwonwu might have revealed of Adetutu’s personality in this painting, but also the fact that Adetutu sat for two other portraits, which the artist obviously was not sentimental about. These thoughts got me closer to the belief that this painting might be special because the artist had infused it with his personal ideology.

Let me illustrate this point with a passage from the novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde, where a famous artist said he could not exhibit a portrait that his friend had just praised as his best work because he had put too much of himself in the painting. He explained,

Every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter. The sitter is merely the accident, the occasion. It is not he who is revealed by the painter; it is rather the painter who, on the colored canvas, reveals himself. The reason I will not exhibit this picture is that I am afraid that I have shown with it the secret of my own soul.

In a similar vein, I romanticize that Tutu is really not about the sitter, Adetutu Ademiluyi. Instead, it is a summation of Ben Enwonwu’s hopes and fears for the African expression. He had come in contact with the anti-colonial cultural and political movement, Negritude, while studying in Europe, and, identifying with some of its philosophies, he gravitated to Paris, heart of the Negritude movement, where he mingled with its leaders and other African and Caribbean members. I surmise that, employing the portrait, Tutu, as a visual interpretation of this ideology, he portrays his veneration of the black woman as the embodiment of the African ideal. He reveals his unabashed pride in African aristocracy ignoring European standards; his hope for an African art that responds to contemporary life and times but is also aware of traditional, local and global influences; and his defiance of the criticism that his art is ambivalent and influenced by Western art—as he told the BBC in 1958,

I will not accept an inferior position in the art world. Nor have my art called African because I have not correctly and properly given expression to my reality. European artists like Picasso, Braque and Vlaminck were influenced by African art. Everybody sees that and is not opposed to it. But when they see African artists who are influenced by their European training and technique, they expect that African to stick to their traditional forms … I do not copy traditional art…

Of course, it was easy to come to this conclusion when I know that between 1972 and 1975, Enwonwu devoted a large number of works to exploring how the ideology of Negritude might be usefully interpreted in visual imagery. This resulted in the Negritude series. While those paintings followed the same form, Tutu is different and might have seemed to him the essence of what he’d called the African philosophy of Negritude. On my part, I just want to believe Tutu means much more than the portrait of a pretty Yoruba princess.

Discussion about this post