By Abba Ali

As the elections draw nearer, there have been lots of political calculations in the polity, especially at the state level. This trend is more pronounced in states where the governor is not seeking reelections. And as natural, the struggle to succeed him takes center stage. In times past, I have advocated in some of my writings that there is the need for power rotation to stem disaffection amongst ethnic groups in Nigeria due to our heterogeneous nature.

This piece was conceived after an encounter with the 1995 Draft Constitution. I was amazed as to the content and how it would have saved us a whole lot of issues as regards political leadership in Nigeria. Section 229 (2) of the 1995 draft constitution states that “The Office of Governor, Deputy Governor and Speaker of the House of Assembly shall rotate among the three Senatorial districts in the state.”

This is explicit and common sense. The Draft recognized the remarkable complexity of the Nigerian nation. It envisaged that somewhere along the line ‘majority’ and ‘minority’ would flex muscles in the issue of governance and subsequently it made provision by advocating power rotation amongst the three senatorial districts in a state. In my opinion, it was calculated to foster a stable polity within which all actors could genuinely feel a sense of belonging and which would elicit the collaborative efforts to move the state forward.

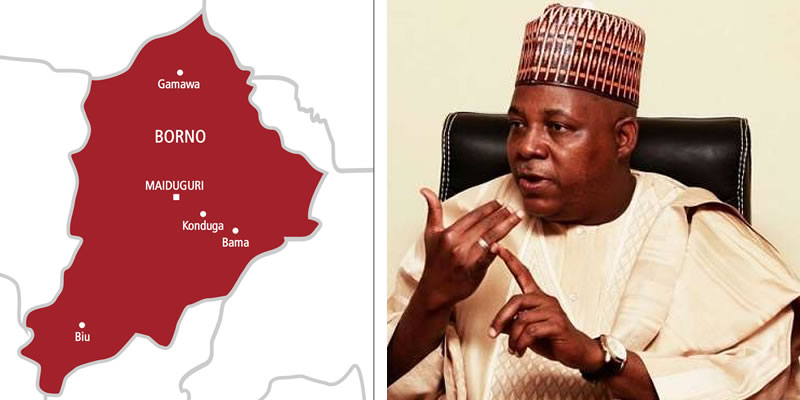

This is where my emphasis stems from the politics of Borno State. It is bad enough that the state has seen the worst of times regarding the impact the Boko Haram Insurgency has had on it socio-economic life. So much so that all that is desired for the state now is healing and meaningful development.

As background, since the creation of Borno state in 1976, it had six civilian governors namely, Mohammed Goni, who was governor from 1979 to 1983 during the second republic, Ashiek Jarma who was elected governor and was in office before the military takeover in 1983. From 1992 to 1993, Maina Maaji Lawan was governor of the state. He was succeeded by Mala Kachalla in the fourth republic (1999-2003). He was replaced by Ali Modu Sherrif, and then the incumbent Kashim Shettima.

The interesting thing about the history of Borno state is that the governorship stool in the state had been rotated between Borno Central and Borno North Senatorial districts, leaving Borno South in limbo and out of the equation. The first civilian governor of the state, Mohammed Goni is from Mobbar Local government area in Northern Borno, Ashiek Jarma, who succeeded him was also from Northern Borno Senatorial District. Maina Maaji Lawan is also from Northern Borno Senatorial district. Mala Kachalla, was from Borno Central, while Ali Modu Sherrif is from Borno Central. And the incumbent governor Kashim Shettima is also from Borno Central.

From the above analysis, it is evident that there has been an unholy understanding between Northern Borno and Borno Central Senatorial Districts in the state. It is also apparent that Southern Borno has been left out of the power equation. Some political analyst would say politics is a game of numbers hence the distribution of power in the state, as most states in Nigeria. But I beg to differ on this school of thought because as a historian, one of the causes of violence in every human society is when there is a sense of injustice or the lack of a level playing ground for all to express their rights.

I have longed frowned at the proponents of the number game in politics because it has not translated to meaningful development in any way, especially at the state level. The case of Borno State is peculiar given its fragile nature resulting from the years of conflict that has caused untold hardship and destruction on the citizens of the state. This has resulted in mutual suspicion amongst citizens of the state, and the current political arrangement of leaving one Senatorial zone entirely out of the power equation might be another time bomb waiting to happen.

Like I mentioned earlier, Southern Borno is yet to produce a governor since the creation of the state since 1976 when the state was created. The simple answer to this is that of ethnicity where the Kanuri’s see the governorship of the state as an entitlement forgetting that the issues of marginalization and agitations by ethnic minorities breeds suspicion, distrust, heightens ethnic tensions and may eventually lead to conflict over the sharing and allocation of power and resources.

Given this, as well as the implications of apparent conflict over power sharing, the ethnic question demands continuous examination if efforts to achieve a better Nigeria are to succeed. Conflict as an aspect of ethnicity is more pronounced in societies where the inter-ethnic competition for scarce resources is the rule, mainly when inequality is accepted as a given. In this type of set-up, no group wants to be consigned to the bottom of the ladder. Hence groups exploit every means in a bid to remain at the top. In a democratic society, where the right to choose is a guiding principle, ethnic groups may show extreme interest in who gets what, how and when. And this what is playing out in Borno State at the moment.

While it might sound politically correct to some that Southern Borno is not entitled to have a shot at governance, I dare say it is politically and morally incorrect looking at the broader implication for a state as fragile as Borno. The state needs healing, but in an attempt to bring about the healing process, justice and fairness must first be seen amongst the political elites in the state.

As a flashback, ethnic factors may be seen as responsible for the confusion and distrust that marked this first attempt at democracy, especially towards the end of 1965. Given the intensity of ethnic sentiments and sectionalism, the first republic was destined for a brief life. During the next republic (1979-83), one would have hoped that the politicians had learned a few lessons from the errors made in the 1960s. This was not to be, for the second republic was also debilitated by ethno-regional conflict.

From the preceding, it is clear that democracy in Nigeria can only endure if perceptions of marginalization and acts portending the marginalization of ethnic groups or zones are directly confronted. While ethnic cleavages may endure, practices and actions that give the impression that an ethnic group or zone is being marginalized or singled out for discrimination should be curbed.

It must, therefore, be argued that there is the urgent need to confront the realities of ethnic minorities, who have thus far been neglected in the dynamics of the Nigerian power and resource game. Ethnic minorities are full members of the Nigerian federation and should be treated as thus. The Borno state case presents us with a vivid example that has left Borno South out of the scheme of things since 1976. Borno Central and Borno North have found it imperative to continue to dominate and by extension suppress the yearning and aspirations of Borno South. This is wrong.

READ: 2019: Group gives Gov. Shettima reasons Southern Borno must produce his successor

In my opinion, the time for Borno South to have a shot at governance is now. And as I have enumerated earlier, healing can only take place in an environment of justice and fairness. It is hoped that the political actors in Borno state can come to a consensus to ensure that the building tension is nipped in the bud. We are all witness to the level of destruction the state has experienced. That is not a road we want to go through again, never. I think Borno South is deserving of a shot at governance.