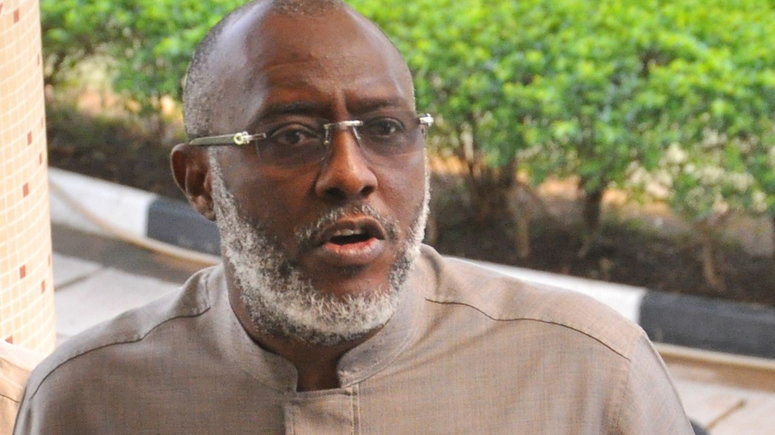

The Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) has urged the Supreme Court to reverse the December 16, 2020 judgement of the Court of Appeal, Abuja, which voided the conviction and sentencing of the former National Publicity Secretary of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), Olisa Metuh and his firm, Destra Investments Ltd.

In three separate notices of appeal filed by its lawyer, Sylvanus Tahir, the EFCC also wants the apex court to void the Appeal Court finding that former National Security Adviser (NSA), Mohammed Dasuki was indicted in the February 25, 2020 judgment by Justice Okon Abang of the Federal High Court, Abuja.

Justice Abang had, in the judgment, convicted Metuh and his firm on the offence of money laundering, sentencing the politician to seven years in prison and ordered that the company be wound up.

But, on appeal by Metuh and Destra, the Court of Appeal revered the judgement on the grounds that the trial judge exhibited bias in his handling of the case and ordered a retrial.

The Court of Appeal, also in a third appeal by Dasuki, marked: CA/A/CR/319C/2020, the appellant upheld the appeal and set aside some aspects of the trial court’s judgment which it said indicted the ex-NSA.

In the two notices of appeal filed against the judgement of the Appeal Court in relation to Metuh and Destra, the EFCC raised 10 grounds of appeal.

On the first ground, the EFCC argued that the Appeal Court erred in law when it failed to consider its argument against the competence of grounds 12 and 14 of the appeal by Metuh.

EFCC, while contending the the Appeal Court did not hear the appeal on the merit, argued that had the court considered dispassionately its arguments grounds 12 and 14 would have been struck out and the entire appeal heard and determined on the merit.

It argued that Metuh’s complaints in grounds 12 and 14, on which it claimed the Court of Appeal based its decision, “was not based on the reasons for the judgment of the trial court, but on the comments, remarks, views and opinion expressed by the trial judge, which could not have given rise to competent grounds of appeal.

“The appeal was decided solely on the issues distilled from the said grounds 12 and 14 and the judgment of the trial court was nullified, without due consideration of other issues submitted by the parties for determination.”

The EFCC further argued that the Court of Appeal erred in law and occasioned a gross miscarriage of justice when it adjudged the comments, remarks, views and opinions expressed in the judgment by the trial judge as amounting to bias.

It argued the comments, remarks, views and opinion of the trial judge were expressed after the conviction of the appellant, hence the views of the judge had to bearing on the merit of the case.

The EFCC contended that the trial judge, under the law, was at liberty to make the remarks he made, which did not detract from the judicial duties the court carried out.

It also faulted the Court of Appeal for failing, as an intermediate court, to consider other issue submitted by the parties for determination and considered only two issues, but labelled the others as academic and failed to pronounce on them.

“The law is that where an intermediate appellate court rests its decision one of the issues, it should also express its views and pronounce on the other issues identified for its determination. The court bellow failed to do so in this appeal.”

It further argued the Appeal Court was wrong to have nullified the judgement of the trial court when the appellant failed to raise any cogent evidence of judicial bias against the trial judge.

“In making the order of retrial, the lower court did not consider the problem of availability of witnesses. An order for retrial is not made off hand or unadvisedly, but based on established principles, which the court below failed to take into consideration,” it said.

In the third notice of appeal filed against the Appeal Court’s decision in relation to Dasuki, the EFCC raised for grounds against the judgment.

It faulted the Court of Appeal for allowing the appeal by Dasuki, who was not a party in the case decided by the trial court.

The EFCC contended that under the law, the right of appeal in criminal proceedings could only be exercised by a party to the proceedings, either an accused, a convict or the prosecutor.

“The court below lacked the requisite jurisdiction to have entertained the appeal by a non-accused, who was never prosecuted, convicted or sentenced by the trial court,” it added.

The EFCC further faulted the Court of Appeal for considering Dasuki’s lawyer when it had already, in the appeals by Maetuh and his firm, nullified the same judgment appealed against by the ex-NSA.

It therefore prayed the Supreme Court to either set aside the Appeal Court’s judgment and restate that of the trial court, or invoke its power under Section 22 of the Supreme Court Act to “do what the Court of Appeal ought to have done in going into the merit of the case as determined by the trial court to decide if the appeal should have been dismissed or not.”

In the alternative, the EFCC wants the Supreme Court to set aside the judgment of the Appeal Court and remit the case back to the court for its President to constitute a fresh panel to hear it on the merit.