A Public Health expert, Gabriel Adakole, has urged stakeholders in the health sector to intensify surveillance on Marburg disease, saying its clinical diagnosis can be difficult because its symptoms are similar to malaria and typhoid fever.

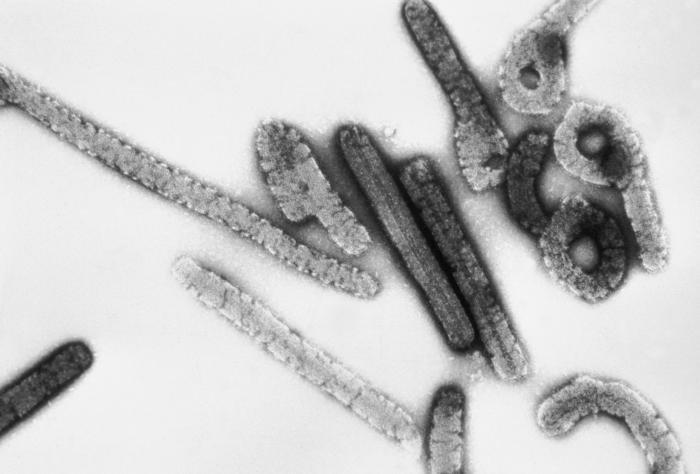

Adakole told the News Agency of Nigeria (NAN) in Abuja that Marburg is a highly infectious viral hemorrhagic fever in the same family as Ebola.

NAN reports that Ghana’s Ministry of Health confirmed two cases of the Marburg virus disease on Sunday after the virus was found

in the blood of two deceased patients who had diarrhea, fever, nausea, and vomiting.

It was Ghana’s first case, and the second time the disease had been detected in West Africa. However, nearly 100 people have been placed under quarantine after being identified as potential contacts.

According to the public health expert, the disease is initially transmitted to people from fruit bats and spreads among humans through contact with the bodily fluids of infected people.

He said that “the marburg virus is genetically unique zoonotic; a hemorrhagic fever virus of the Filoviridae family of viruses; the six species of Ebola virus were the only other known members of the filovirus family.”

He said that Ghana had confirmed cases of the virus and Nigeria and other neighbouring countries had been placed

on high alert as there were no approved vaccines or treatments for the disease.

The expert said “Marburg causes serious illness and can be lethal, with fatality rate from past outbreaks varying from 24 per

cent to 88 percent, depending on the virus strain and quality of care.”

According to him, once someone is infected, the virus can spread easily among humans through direct contact with

bodily fluids such as blood, saliva, or urine, as well as on surfaces and materials.

He added that “it begins suddenly and its symptoms include high fever, muscle pains, bleeding, severe headaches, diarrhea, and vomiting blood.

“There are no vaccines or treatment approved for the disease but supportive care like rehydration and the treatment of specific symptoms can improve outcomes.”

Adakole said that close relatives and health workers were mostly vulnerable, alongside patients, and bodies remained contagious

at the burial when a person becomes affected.

The expert said that infected persons may experience a non-itchy rash on the chest, back or stomach around day five after infection.

He noted that in fatal cases, death usually occurs between eight and nine days after the onset of the disease, with severe blood loss and

multi-organ dysfunction.

He added that “however, supportive care can improve survival rate such as rehydration with oral or intravenous fluids, maintaining

oxygen level, using drug therapies and treating specific symptoms as they arise.”

He, therefore, urged relevant agencies to leverage available evidence such as the downwards of the Travel Protocol from Ghana

and other nearby countries.

Adakole said government should focus more on surveillance, genomic sequencing and surge testing, while health workers

should remain vigilant in times like this.

NAN recalls that Matshidiso Moeti, WHO Regional Director for Africa, had commended Ghana’s “swift response”,

warning that “Marburg can easily get out of hand, without immediate and decisive action.”

Moeti said, “WHO is supporting health officials in Ghana and has reached out to neighbouring high-risk countries and they are on alert.”

Meanwhile. the first cases of the virus were identified in Europe in 1967. Two large outbreaks in Marburg and Frankfurt in Germany,

and Belgrade and Serbia led to the initial recognition of the disease.

At least seven deaths were reported in that outbreak, with the first infected persons being exposed to Ugandan imported African green

monkeys or their tissue while conducting lab research.

Beyond West Africa, previous outbreaks and sporadic cases were reported in Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, South Africa, and Uganda.

The virus killed more than 200 people in Angola in 2005, the deadliest outbreak on record according to the global health body.