Funmilayo Ransome Kuti, mother of music maestro, Fela, fought against the Alake of Egbaland in present day Ogun state between 1946 and 1949.

Egba women were displeased with various actions of the Alake, some of which were the introduction of taxation on women’s produce and non-representation in the sole native authority.

She led a massive protest against the Alake which spanned a period of almost four years culminating in the self exile of the monarch.

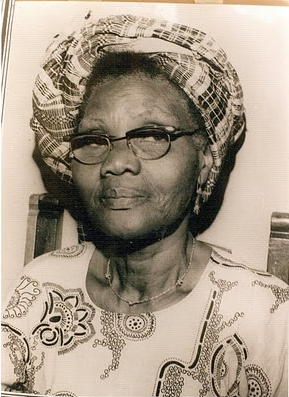

Born on October 25, 1900 in Abeokuta in present day capital of Ogun state, South west Nigeria, Funmilayo Ransome Kuti, was a women’s rights activist and a traditional aristocrat in Nigeria. She was one of the most prominent women leaders in her generation. She was the first woman in the country to drive a car. Following her doggedness, she was described as the doyen of female rights and the mother of Africa. She was a very powerful force advocating for the Nigerian woman’s right to vote and fought for women’s recognition in government.

She was the mother of the activists Fela Anikulapo Kuti, a musician; Beko Ransome Kuti, a doctor; and Professor Olikoye Ransome-Kuti, a doctor and health minister. She was also grandmother to musicians Seun Kuti and Femi Kuti. Her father, Daniel Olumeyuwa Thomas, was a son of a returned slave from Sierra Leone, who traced his ancestral history back to Abeokuta. He became a member of the Anglican faith, and soon returned to the homeland of his fellow Egbas. She was raised by parents who valued education and became the first girl-student admitted to Abeokuta Grammar School, hence, her nickname Beere which means first girl in Yoruba.

She later went to England for further studies. She soon returned to Nigeria and became a teacher. On 20 January 1925, she married the Reverend Israel Oludotun Ransome-Kuti. He also defended the commoners of his country, and was one of the founders of both the Nigeria Union of Teachers and of the Nigerian Union of Students.

Funmilayo Ransome Kuti received the national honor of Member of the Order of the Niger in 1965. The University of Ibadan bestowed upon her the honorary doctorate of laws in 1968. She also held a seat in the Western house of chiefs of Nigeria as an Oloye of the Yoruba people.

As a strong women’s rights activist, she provided strong leadership for women in the 1950s. She founded Abeokuta Women Union (AWU), an organization with more than 20,000 women membership and through which she championed her fight against discrimination against women and other anti-women programmes.

Ransome Kuti, in her vociferous nature, launched the organization into public consciousness when she rallied women against price controls that were hurting the market women. Trading was one of the major occupations of women in the Western Nigeria at the time.

London, May 1937

In 1949, she led a protest against the native authorities, especially against the Alake of Egbaland. She presented documents alleging abuse of authority by the Alake, who had been granted the right to collect the taxes by the colonial administrators. Oba Ladapo Ademola, the Alake of Egbaland with 89 crowns, became the king of the Egbas in 1920.

It was learnt that in 1918, Governor-General Lugard had introduced a system of direct taxation and created the Sole Native Authority which was a form of indirect rule whereby the traditional rulers acted as agents for the colonial government. The Sole Native Authority, equivalent to today’s local government, was headed by the Alake of Egbaland.

It had far-reaching powers and all the previous checks and balances on the power of the Alake were eroded under the indirect rule system as kingmakers, chiefs and priests who could act to limit the abuse of power of the Alake were now dependent on the Sole Native Authority for their appointment to advisory councils.

Information Nigeria reports that prior to the advent of the British, women had participated in politics and had their own representatives. The most important, was the Iyalode on state councils whose duty was to protect and promote women’s interest. When the British came, it never occurred to them that women had any significant role and so they never made any provision for women. Nevertheless, some women titles like Iyalode and Erelu remained but they lacked power and influence.

The aching issue for the Egba women was taxation. Having been subjected to tax by the colonial government, they provided as much as one-half of district revenues. Yet, they had no direct representation on the Sole Native Authority council, a situation they abhorred so much.

Further, the manner by which taxes were collected was often through insult, violence, chasing of women, beatings and stripping of young women ostensibly to assess their age.

As time went on, complaints increased, reaching a point where women decided that their only chance to gain redress of their grievances was a more militant approach. They considered the tax as foreign, unfair and excessive. They also objected to the method of collection. This was the one issue which catapulted Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti into the political limelight, first in Abeokuta and then in Nigeria.

In 1923, Ransome-Kuti organized a group of young girls and women into the Abeokuta Ladies Club. The group was made up of western educated middle class and mostly Christian women who concentrated on crafts and social etiquette.

Between 1943 and 1944, the Abeokuta Ladies Club regrouped and expanded to include market women who had approached Kuti to explain their ordeal to her. Most of these women were uneducated and it was at this point that Kuti began her political activism which was aimed at raising the standard of womanhood in Abeokuta, encouraging learning among the adults and thereby wiping out illiteracy from the land.

Funmilayo felt deeply pained after hearing the exploitation and the hardship the colonial masters and the native authority had subjected the people to and the harassment from the police officers in Egbaland. Reports say she discovered that the Alake, the traditional ruler of Abeokuta was diverting confiscated rice to his own stores, selling it and pocketing the profits for himself. These rice were confiscated from the women by the government.

In 1946, the burden of taxation became unbearable and the Abeokuta ladies club metamorphosed to Abeokuta Women Union. This was designed to challenge both colonial rule and the male-controlled structure. Through the union, they opposed price controls and imposition of direct taxation, engaged in press campaigns and mobilized so much pressure against the Alake.

The Abeokuta Women Union was a well organised and disciplined organisation. Mass refusal to pay the tax combined with enormous protest led to brutal response from the authorities as tear gas were deployed and beatings were administered. Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti ran training sessions on how to deal with this threat, teaching women how to protect themselves from the effects of tear gas and how long they had to throw the canisters back to the authorities.

Abiyamo, a Nigerian blogger, reports that under the leadership of Funmilayo, the women demanded exclusion of direct female taxation of Abeokuta women. They also demanded for the representation of women in local politics and governance. Funmilayo was of the view that no important decision could be made without the involvement of women.

When her protests began, the Alake did not take her serious. She was seen as a typical women ranting. They under estimated her believing she would go nowhere. But that was their undoing. From 1946 to 1948, she led women in protest against women taxation, non-women representation in the native authority. She even led protest against some of the business interest of the Alake of Egbaland.

She was persistent in her demand for women rights and representation in the native authority. She called for taxation of expatriate companies, abolition of native authority and replacement with representative government where the interests of women were well represented.

She sent various petitions to the Alake but her petition fell into deaf ears. In 1946, the group sent a delegation to the Alake to present their demands but rather than assuage the pains of the women, the Alake went further to increase the taxation on the women.

At a point of her protest, the royal court issued an edict that all women who owned property must pay income tax. Following the repressive decree, she termed the Alake a dictator. She lashed out at the royal court, calling her women to prepare for war.

In October 1946, about 1000 women protested to the palace of the Alake but the British police applied teargas on the women, beat them mercilessly and dispersed them from the palace. The anti-tax protest was a long one with Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti at the head leading the women in the struggle.

In 1947, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti refused to pay her taxes and was arrested. At her arraignment where she pleaded “not guilty,” thousands of women congregated at the courthouse to demonstrate their support for her. The next year, she again refused to pay her taxes while the protests went on.

According to Dunamis, another Nigerian blogger, the women saw the action of the Alake as their strength, it gave them more morale and will power to continue the protest in a more aggressive way this time. During this time, they released a document they called the AWU’s grievances and therein, they penned down all their accusations against the Alake of Egbaland and the sole native authority.

The next form of protest took a new format, it overwhelmed the Alake and community at large. It lasted for over 48 hours at the palace of the Alake. It started on 29th of November 1947 to the morning of 30th November with over 10,000 women fuming outside the palace of the Alake under the leadership of Funmilayo Ransome Kuti

Several tall talks were chanted coupled with numerous incantations to rebuke and demean the Alake. At this time, the British authority tried to seek solace from both parties. They implored the king to hold an olive branch, to ensure the community is at ease, they were feeling uncomfortable already due to the die-hard attitude of the women.

They further made false promises to the women that the bone of contention, the tax, would be suspended and the final outcome about would be communicated in three days. When the women noticed it was just a fallacy, they geared up and marched to the palace with over 10,000 infuriated women for the protest.

They demanded the release of their detained members. This took over two days in a spot and uproar outcry of justice and respect for the women. This started on the 8th of December and as at 10th the detained women were released.

In January, 1948, Kuti was banned from the palace for insulting the Alake and the British administration supported it. Administrative attempts to woo away the Abeokuta Women’s Union executive from its support of Kuti failed. They also refused to attend any meeting without Kuti.

By April, the women were determined to get rid of the Alake and obtain their demands, one of which included that the Alake be removed from office. They continued their demonstration and vowed to go on the streets unclad, an action which was a taboo in Egbaland.

Imbibed with great powers, and the women were instructed to go home, before evil spirits overcame them. When the women shrank back in fear, Funmilayo Ransome Kuti, grabbed the stick, waved it around, noting that that women now had the power before taking it with her, displaying it prominently in her home.

This action gave her, a reputation of fearlessness and courage, which led 20,000 women to follow her to the home of Alake of Egba land. As the women protested outside the king’s palace, they sang in Yoruba; “Alake, for a long time you have used your penis as mark of authority that you are our husband, today we shall reverse the order and use our vag*na to play the role of husband.

With her continuous protests coupled with series of letters calling for the removal and dethronement of the Alake of Egbaland, the king voluntarily decided to abdicate the throne of his forefathers and went into self-exile. He remained that exile for one year until he returned to his throne in 1950 but by the time he was back as king, he did not make the mistake of challenging the women of Egbaland or their fearsome leader, Funmilayo Ransome Kuti.

In her old age, Funmilayo’s activism was overshadowed by that of her three sons, who provided effective opposition to various Nigerian military juntas. In 1978, Funmilayo was thro

ebalsblog…from a third-floor window of her son Fela’s compound, a commune known as the Kalakuta Republic, when it was stormed by one thousand armed military personnel. She lapsed into a coma in February of that year, and died on 13 April 1978, as a result of her injuries she sustained from the fall.

Discussion about this post